“Endurance athletes, by definition, endure. They endure long hours of training, the privations of a monastic lifestyle, and all manner of aches and pains. But what endurance athletes must endure above all is not actual effort but perception of effort. this is the phrase that scientists now use to refer to what athletes normally describe as “how hard” exercise feels in a given moment, and it represents the central concept of the psychobiological model of endurance performance.”

– Matt Fitzgerald (“How Bad Do You Want It?: Mastering the Psychology of Mind Over Muscle“)

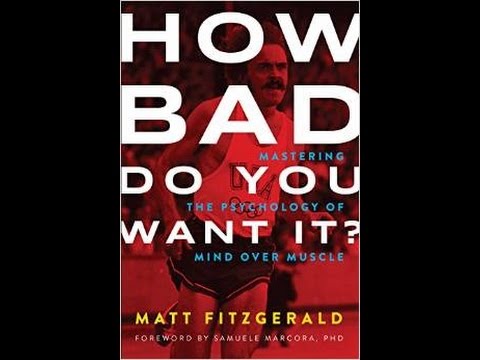

In the short time since finishing Matt Fitzgerald’s “How Bad Do You Want It?: Mastering the Psychology of Mind Over Muscle,” I’ve mentioned the book to several people, and the first thing I say is that I think the book is better than the title. What I mean is that I think the question in the title puts the focus on the “it” — the desired outcome of all our striving. But the book itself seems primarily concerned with something that I believe is more subtle and complex, and that is the question of how badly we want to AVOID the discomfort that stands in the way of our reaching our goals.

In his other books, Fitzgerald has written extensively about the role of the mind in endurance activities. In this book, however, he is not especially interested in the laying out the extensive case for a mind-based approach to training and racing. Instead, he wants to illustrate the role of mind by telling stories, specifically stories about the best endurance athletes on the planet.

In his introduction, Fitzgerald writes:

“Endurance sports are largely about discomfort and stress; hence they are largely about coping. In a race, the job of the muscles is to perform, The job of the mind is to cope… Some methods of coping are more effective than others. Faking an injury to avoid the discomfort of completing a race […] is one example of an ineffective coping method. Drawing inspiration from elite athletes to embrace greater levels of discomfort […] is an example of a more effective coping method.”

Elsewhere he tells us that this is not a training manual or a how-to book, and that he will not be providing lists of exercises or a program for improving mental fitness. Instead, each chapter introduces an athlete or a team, and describes their development leading up to moments of crisis, some that result in failures, some that become breakthroughs. The chapter titles capture the big ideas, such as, “A Race is Like a Firewalk,” “The Art of Letting Go,” “The Gift of Failure,” “Is it worth it,” and so on, but the ideas are embodied by the specific athletes he follows.

For example, the first chapter takes as its inspiration Sammy Wanjiru’s larger-than-life victory at the 2010 Chicago Marathon, a performance that reason tells us should have been impossible. When he came back to win after being dropped not once but three times by one of the best runners on the planet, his coach said “It was the greatest surprise I have ever seen in my life.” Fitzgerald takes that race as a jumping off point to talk about the psychological factors that enable the weaker, more fatigued athlete to vanquish the stronger one. He goes on to compare a race to a fire walk, where taking each step requires more mental fortitude than the one before. Tolerance of the progressive discomfort determines how close the athlete comes to the limit of their physical capabilities.

Another chapter is about how Greg Lemond overcame a near-fatal hunting accident to return and win the 1989 Tour-de-France by overtaking Laurent Fignon in the final stage, a short time trial into Paris. There is another chapter about another Tour winner, Australian cyclist Cadel Evans. There are chapters about triathletes Siri Lindley and Paula Newby Fraser, runners Steve Prefontaine and Jenny Simpson (née Barringer), Olympic rowers Nathan Cohen and Joseph Sullivan, the U.S. team that beat the Kenyans at the 2013 World Cross Country Championships. It is a library of case studies of how great athletes learned to cope with personal obstacles and the quite outrageous demands of their sports.

Fitzgerald is a great story-teller, and a reader could enjoy the book for the stories alone. But every account is meant to be an example of what the mind is capable of. In that sense, this is really a book about great athletic minds and great mental fitness. I found that after each chapter I wanted to rush outside and tackle a really hard workout or really long run to see how my mental fitness would stand up.

Beyond that immediate response, I suspect that “How Bad Do You Want It” is well on its way to bending my way of thinking about training in a more permanent way. It’s hard not to conclude, after reading about the athletes in Fitzgerald’s canon, that the specific physical training is never the whole story, maybe not even the most important one.

Sounds like another great Fitzgerald book I’ll need to read. I’ve found especially as I become a more “mature” runner (wink wink) the “how bad do I want it” question is asked more often. Thanks so much for the review!

Thank you very much for the comment, Marcia!

You make a great point. Our motivations change a lot with the passing years, and what I MOST want now is to be able to keep going, without risking significant down time. I’m less and less likely to want to test my limits, if the penalty is being sore or injured for an extended time. I think this is a real balancing act for me, and perhaps for most older athletes. Anyway, overcoming those fears seems like another element of what Fitzgerald calls mental fitness.