“Churches and trains

They all look the same to me now

They shoot you some place

While we ache to come home somehow”

– Gregory Alan Isakov, Amsterdam

I was genuinely puzzled when people would tell me to “have fun” in Japan.

Is travel supposed to be “fun?” Travel is hard!

Of course, I didn’t say that out loud. Instead, I thanked them for their good wishes, and internally made an effort to quell my doubts and anxieties about the whole project. I found myself envying my well-wishers and others for whom travel is a sparkling delight, an intensely pleasurable opportunity to explore new and exotic locations. I wish I felt the same, but I looked ahead to my trip with much the same feeling I would have if I was planning to run a marathon. I was fairly sure it would be worthwhile, after it was over, but I didn’t expect to have fun.

I wonder sometimes what makes me that way. I seem to live my life suspended between two contradictory imperatives: on the one hand, an instinct for caution and a desire for the the familiar and the routine (confession: I once ate exactly the same thing for lunch, every day for an entire school year….); on the other hand, a deep need to throw myself into unfamiliar situations, as if daring my cautious self to deal with its fears of the unknown.

In spite of, or maybe because of that contradiction, I really loved being in Japan, even though it was hard and the trip started off badly. I’m not sure that the trip taught me that much about the country — I was there for such a short time and saw so little in the time I was there — but what I did experience made a strong, positive impression.

When people ask, “How was Japan?” I think of my friend who told me that unpacking the suitcase might take only half an hour, but unpacking the experience might take years. So I’m not going to try to sum everything up. Instead, I’m going to close this Japan Journal by writing about three things that were most meaningful to me.

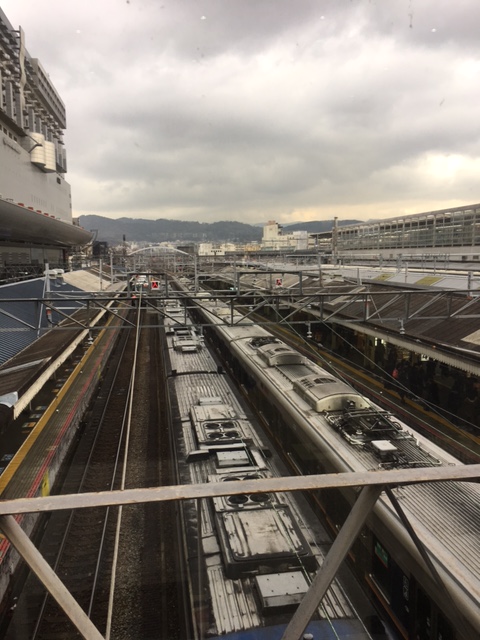

The Trains

I am not ashamed to say that I fell completely in love with the Japanese railway system. From the streetcars that rumbled on private lines through Otsu, to the metro trains running below the streets of Tokyo and Kyoto, to the punctual and modern express trains of the JR system, to the iconic Shinkansen whose speed magically diminished the distance between the major cities, I loved riding the trains. I could have spent my entire time in Japan riding the trains and would not have thought it a waste.

My love of trains had an interesting emotional angle. The longer I was in Japan, the more I found myself thinking about my Dad, who had always loved trains. I knew from the train magazines and videos that he accumulated during his life that it was a passion of his, but I didn’t really share that passion with him while he was alive, and it made me a little sad that I couldn’t share all my railway-related observations with him now.

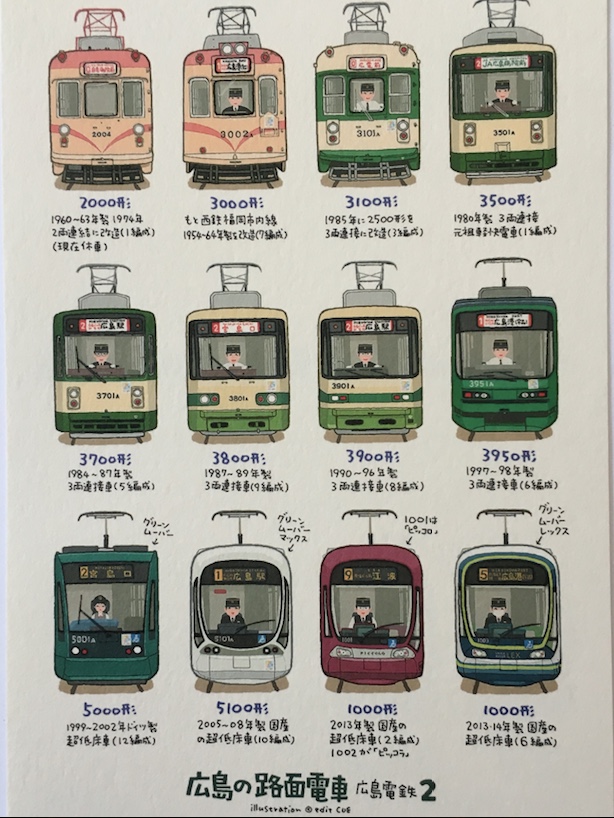

I remember seeing a postcard for sale in the gift shop for the Heiwa museum in Hiroshima with drawings of streetcars, along with the years that they had been introduced to the city’s transportation network. I bought the card even though I knew that I there was no one to send it to who would appreciate it the way my Dad would have.

A final note to suggest the imaginative potential of trains in Japan:

After returning to the U.S., I re-read (in translation, of course) a detective novel called “Points and Lines,” written by Japanese author Seicho Matsumoto. The mystery and its solution depend deeply on the details of Japanese train schedules. The story also contains a passage that evokes the inherent mysteries in railway timetables:

“At this very moment.. trains are coming to a stop at certain stations in Japan. People from every walk of life and with varied backgrounds are getting on and off these trains. I close my eyes and picture the scene. If I check the time and the station I may even learn how trains pass each other and at what hour… How and when trains connect or pass each other is deliberate and planned, but the meeting and parting of passengers is purely accidental. At such moments, I can imagine the ceaseless movements of these thousands as their lives briefly brush past each other in those faraway places. I find more pleasure in my own flights of fancy than in novels born of the imagination of others…”

The Language

If you’ve read previous my previous Japan posts, you’ve already realized that using Japanese was one of my main interests and challenges. I’ve resisted the urge to describe my Japanese ability as “pitiful,” although it sometimes felt like that. But if I’m honest with myself, I was very proud of being willing to try to speak Japanese as much as possible, and I came home with a renewed desire to keep working at it.

But I wasn’t really “working on it,” while I was in Japan. I was using it. To employ another running analogy, it was like the difference between following a training regimen with a coach, versus simply running back and forth to work as a means of transportation.

And I found that, in almost every interaction in which I spoke Japanese, I felt an odd, arms-length connection with the person I was talking to. I didn’t need to say, “I’m a stranger in this country, struggling to figure out where to go and how to survive,” because my effortful and often ungrammatical sentences said all that for me, no matter what words I used. And so every response to my stumbling attempts to communicate was an act of kindness and sympathy and humanity.

Then there was the written language. In my two weeks there, I never lost the habit of staring at every sign, fascinated to recognize some of the characters, and baffled by the others. I probably missed seeing hundreds of more traditionally interesting sights because I was so focused on trying to decode the ads on the trains, or the mysterious writing on vending machines and in shop windows.

The covered mall near our apartment. Every alley was a linguistic paradise.

By the way, there was a lot of English on public signs. Some of it made sense, but some of it was really weird. I submit just one isolated example, the following sign on a small shop in Hiroshima. What does it mean? What is the trick?

The Japanese is fine; it’s the English I don’t understand

The people

I’ve told several people that when I deplaned in Toronto, I was struck almost immediately by the odd and almost unpleasant sound of English, and by the rough way that people talked to you without bowing.

Besides trying to speak in Japanese while I was in Japan, I tried really hard to bow as much as possible. I really liked bowing. At the same time, I suspect that my limited understanding of Japanese culture means that I have an overly-romantic notion of how all this politeness is such a great thing. I remarked to my friend Jonathan that it was probably easy for me, or for any Westerner, to enjoy this highly-civilized tendency of Japanese people to be incredibly nice to foreigners; we’re treated like honored guests, but we’re also forgiven all our natural Western rudeness because, after all, how would we really know how to behave without being Japanese?

I don’t know what it’s like to be raised in a society that puts so much emphasis on proper behavior and on strict social conventions for how to speak and act towards one’s superiors and inferiors. Being ignorant of such things allows me to bask in the politeness without feeling anxiety about it.

But bask I did, and I keep thinking back with pleasure to my interactions with everyone I met, from strangers on the train who tolerated my halting attempts to speak their language, to the many uniformed attendants in train stations who not only explained how to buy tickets, but walked me over to the machine, pressed the right buttons for me, and then guided me to the right platform.

I’ve heard it said that one of the most enjoyable aspects of travel is the people that you meet along the way. I accept this as theory, but being a confirmed introvert, meeting new people is often hard for me. So it feels like a triumph that I have such positive memories of meeting people on this trip: Tyler’s parents’ friends, who spent an entire afternoon driving the marathon course with us, the athlete coordinator, who was always there to help us with questions and requests, Yumi — my guide on the tour of Kyoto, and the friendly marketing professor who shared his lunch with me on the train ride back from Hiroshima.

One of my many guardian angels, Yumi poses with the Pokemon toy that I bought for Lyla and that I dragged all over Japan with me so that I could take pictures to show where he (and I) had been.

Epilogue

On Monday morning, the day after Tyler’s Marathon, I finally managed to sleep past 6:00 a.m., suggesting that after almost two weeks, I had finally fully adjusted to Japan Time — just in time to mess up my internal clock again. I will probably never know why my initial jet lag was so severe, but the experience taught me some important lessons about taking care of myself — about eating, sleeping, and being patient, for example.

I met Tyler and Mariana and Kyoto, and they helped me buy some final gifts, and then made sure I caught the train to Shin-Osaka. It was strange to think that this was the beginning of their month-long vacation, and that they would be in far more exotic places soon. As for me, once I got back to the U.S., I would immediately begin the spring season coaching. So much for the leisurely life of retirement!

My trip home went very smoothly. Instead of an early morning flight, I had an afternoon flight from Osaka to Tokyo, and then a late afternoon flight from Tokyo to Toronto that had me arriving two hours earlier than I departed. After a long, but uneventful layover in Toronto, I flew the last leg to Boston, where Ann picked me up at Logan. I walked in the door at about 11 p.m., and had no trouble falling asleep.

That was a week and a half ago. I’ve now mostly adjusted back to East Coast time, and also managed to adjust to the strange way you people have of interacting without bowing.

I still have to go through all my pictures and organize them, and decide whether to keep all the maps, brochures, and receipts in a scrapbook or toss them. I also need to decide what to do with my ICOCA card that allowed me to go through the turnstiles at train stations without buying a paper ticket. The only reason to keep it would be if I were planning to go back again some day.

It still has almost 1000 yen on it.